"If I Could Not Go to Heaven But With a Party, I Would Not Go There At All."

Daniel Sjursen presents another angle on America's founding story, plus a provocative quote ☝️ from Thomas Jefferson on political factionalism in America.

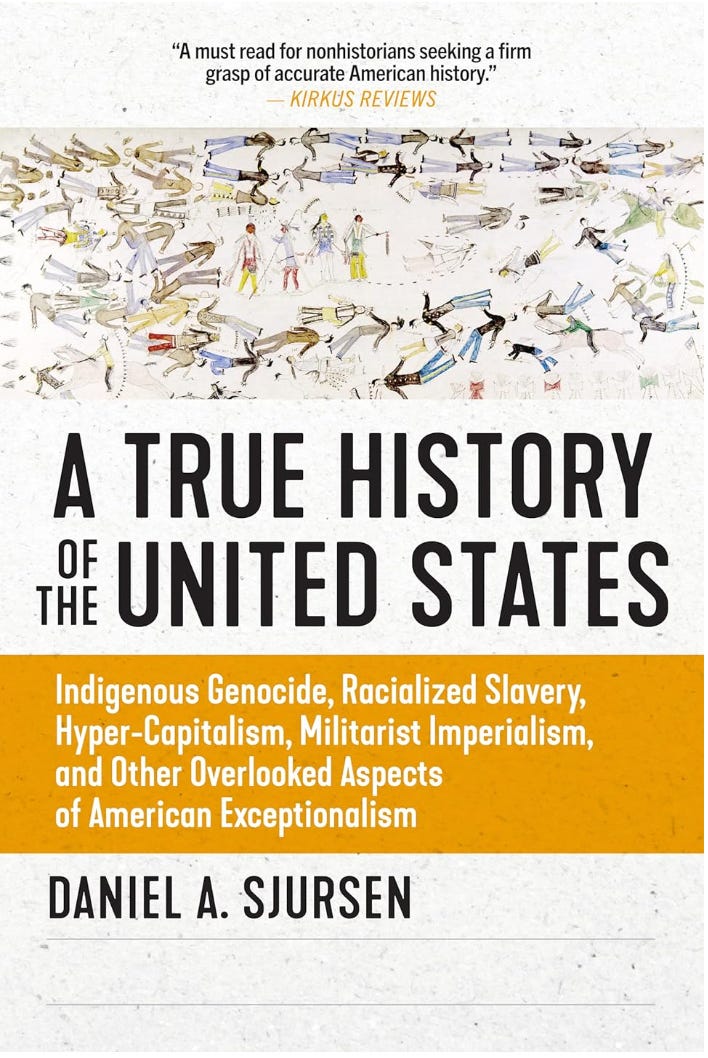

On that same weekend trip to southern Utah, we stopped by Back of Beyond Books in Moab (one of my favorites). The kids and I each picked up a few books, plus a couple games for the road, and for one of the titles in particular I couldn’t help but start as soon as we got back to the camper—A True History of the United States by Daniel Sjursen. No doubt part of what drew me to it, and to start it so soon, was its subtitle—perhaps the longest I’ve ever seen: Indigenous Genocide, Racialized Slavery, Hyper-Capitalism, Militarist Imperialism, and Other Overlooked Aspects of American Exceptionalism. Whew… 😰

The book was shelved cover out; I read the title and subtitle and immediately took it for little more than a leftist critique of all that’s ‘wrong’ with the United States. Still, adamant that we must read and listen to all the sides of a story, I picked up the book for a quick browse of the back cover. I saw the author, Sjursen, is a retired Army officer and veteran of the 20-year “Global War on Terror.” He taught history at West Point while still on active duty, lending credence to his bona fides as an “academic” and “historian.” And though the bibliography is rather short, a glance at the early chapters showed me this book was about something more than simply an activist or revisionist view of American history. It seemed like a book aiming to correct the mythology most of us take for granted about the nation’s founding. And that seemed like a project worth pursuing and supporting.

Sjursen begins the story with dueling narratives about the settlements at Jamestown, Virginia and near Plymouth Rock in present-day Massachusetts. The first group (Jamestown) came to the New World to make money and exploit the continents resources while the latter fled a Church of England believed to be beyond repair. The disparities between these groups are illustrative in the political persuasions we see develop through the wartime period in the 1770s and 80s, the period of Constitutional development and ratification in the 80s and 90s, and even to today’s seemingly intractable ‘left-right’ split. Sjursen makes a point of painting as well-rounded and complete a picture as he can, acknowledging he can never do justice to all the intricacies of what really happened and in what order and what people of the time believed to be true. History, as I’m learning over time, is less about delivering or repeating chronologies and a lot more about adding quality meat to the bone that is the shell of a human story. I’m 100 pages into a 650-page book and already, I want to recommend it.

A Quick Word on Why

Maybe it’s strange—that I’d go so far out on a (at this point) flimsy limb and suggest a book I’m not even a quarter through yet. But why I recommend it at this stage is simple and boils down to one word: perspective. This isn’t a version of the American story you’ve likely heard or read before and that makes it valuable and worth the time.

I don’t want to assume too much about your experience and background, what you’ve read or studied, or whatever else. But on the face of it, Sjursen highlights a number of episodes in America’s earliest years that I don’t remember in any secondary school or university course about the founding of our country or framing of our Constitution. I’m barely through Washington’s presidency yet already am thinking a lot about how our perceived divisions between rural and urban, heartland and coastal, commoner and aristocrat, were sown at the very beginning. Despite Washington’s lament against political parties in his farewell speech (and Jefferson’s own, quoted in the title), we’ve had factions from Day One—including the so-called anti-Federalists led by Jefferson (opposed to too-strong a central government) and Federalists (ironically in favor of a strong central government). It seems of all the battles we’ve fought as a nation, at least one remains that is among our first.

I’m curious where the book will go and how Sjursen diagnoses our current ills and what, if anything, he can offer for the future. No doubt there’s a lot to be worried about these days, and much of it has historical roots going back a couple centuries; but if anything that should also tell us there really is “nothing new under the sun” and maybe…just maybe…that also means the tide will turn yet again toward a better time. To help that along, you should read this book.